Quentin Tarantino believes movies can change the world

Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood (2019)

By Jacob Skubish

This review contains spoilers.

In the dazzling opening scene of Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds, Nazi Col. Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz) questions a dairy farmer in rural France about whether the man is illegally harboring Jewish fugitives. As Landa presses for information, the farmer cautions Landa that all he has heard are rumors. “I love rumors!” Landa squeals. “Facts can be so misleading, where rumors, true or false, are often revealing.”

Inglourious Basterds (2009)

It’s a variation on a common sentiment in the Tarantino universe: what happened matters not nearly as much as the story about what happened. In fact, if there’s one thing that defines the eclectic ouevre of films he has directed, it is his characters’ meta obsession with storytelling. In worlds bereft of justice, telling a compelling story can be the difference between life and death, and becomes its own ethical basis for distinguishing right from wrong.

This idea manifests in Tarantino’s early films through characters who lack information, and must use stories to fill in the gaps. In Reservoir Dogs, a heist gone wrong forces a group of thieves to return to their warehouse hideout and figure out what happened, one story at a time. Despite this reliance on these narratives, Tarantino’s characters are usually aware of just how carefully constructed, and easily manipulated, such stories are. The men in Reservoir Dogs are all strangers to one another, sharing only color-coded monikers with each other (Mr. Orange, Mr. Blonde, Mr. Pink), and know full well how little factual context they have to gauge the veracity of the stories they are being told.

Pulp Fiction (1994)

In Pulp Fiction, Vincent (John Travolta) makes a comment to Mia (Uma Thurman) about hearsay similar to Landa’s in Inglourious Basterds. Vincent is recounting an anecdote he heard about Mia’s husband Marcellus, and Mia challenges him: “Is that a fact?” Vincent’s response implies that he recognizes the distinction between fact and rumor: “No, no. It’s not a fact. It’s just what I heard.”

It was not until Inglourious Basterds, though, that Tarantino started indulging in an entirely different type of factual manipulation: the willful denial of historical events. Landa’s tendency to devalue the truth is nothing new for Tarantino characters, but the gleeful, gruesome murder of Adolf Hitler by insurgent Jewish-American soldiers certainly was. After the success of Basterds, Tarantino went on to craft two more violent historical revisionist films, Django Unchained and the newly released Once Upon a Time … In Hollywood.

When Inglourious Basterds was released a decade ago, it received significant pushback from film critics and historians on the grounds that it was historically ignorant, amoral revenge porn. The New Yorker called the film “appallingly insensitive—a Louisville Slugger applied to the head of anyone who has ever taken the Nazis, the war, or the Resistance seriously.” As Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood engages in similar liberties regarding the 1969 murder of actress Sharon Tate by Charles Manson, it is an interesting question to reconsider: does Tarantino have a right to indulge in these historical retellings?

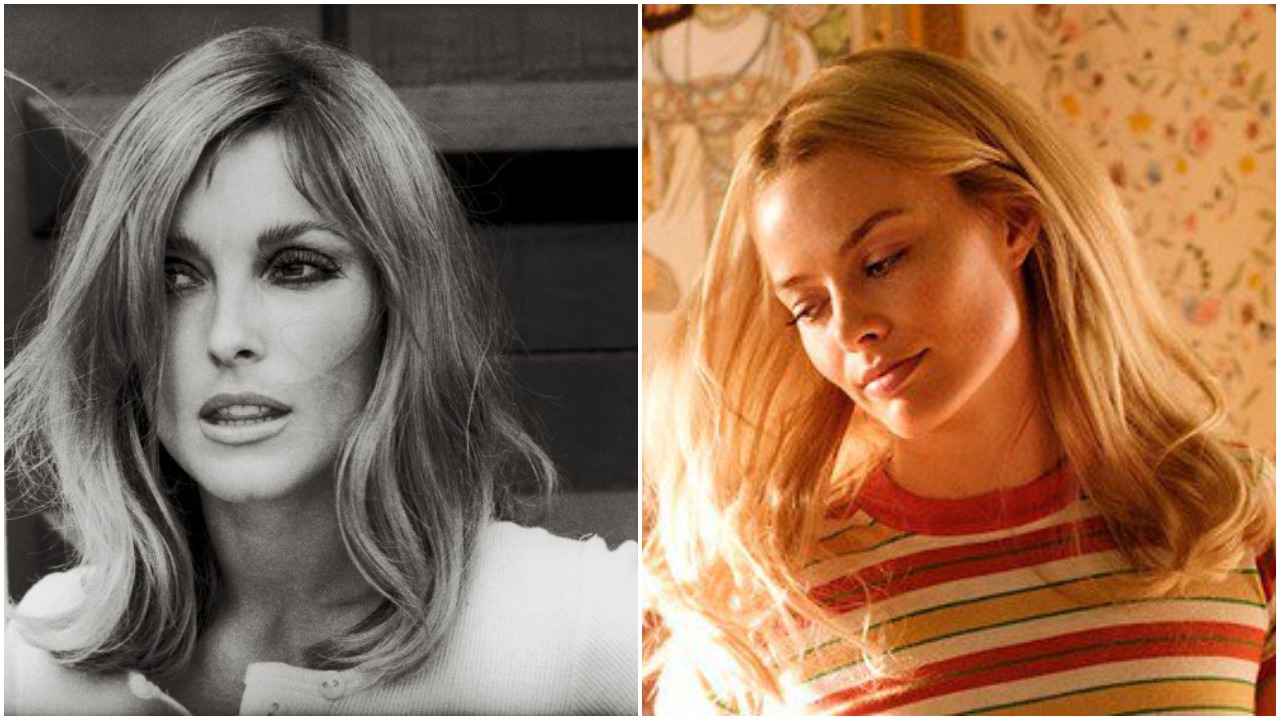

Left: Sharon Tate. Right: Margot Robbie as Sharon Tate in Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood (2019).

The question of whether films have a responsibility to historical accuracy is not a new debate. But the argument is usually a proxy for whether the story tells the Capital-T Truth: does the film’s mishandling of the facts merely mess with the details? Or do the inaccuracies go so far as to change the meaning of the story, or the lesson we are intended to learn? The reason Green Book drew such ire last year was not because a legion of Don Shirley fans came to the defense of the pianist’s historical record; before the film’s release, Shirley was far from a household name. The film was criticized because its manipulation of the facts created the illusion that racism can be solved through a short road trip, and reinforced the on-screen false trope of white saviors. If the details of Shirley’s life had been fudged in an effort to tell a story of Black heroism or excellence, we likely would have obliged.

Tarantino, though, has created an entirely new branch to this debate. His films are willfully inaccurate to the point that they do not just change the details of the story, but the entire outcome of massive historical events. Moreover, it is not always clear why he is doing so. Tarantino is a legend among film geeks for how deeply his movies are laden with references to cinema history, and it often seems like he is only interested in making movies that are…celebrations of movies.

But I think this love for cinema is not separable from Tarantino’s manipulation of history: it is, in fact, the point. It is the adulation of film taken to its logical conclusion: why couldn’t film actually change the world? This is literally the case in Inglourious Basterds, when hundreds of Nazis are killed because film reels are set on fire. Tarantino’s affinity for cinema is not just a craftman’s insular fondness for his trade, but an exhortation that the stories we tell matter.

Of course, many filmmakers feel this way, but choose to tell stories that might caution against future maladies. Get Out, for example, didn’t try to correct America’s racist past on screen; instead, it condemned its racist present, and called out the thinly masked sentiments that portend its racist future. What is the point, then, of erasing what has already occurred?

One theory of Tarantino’s historical revisionist trilogy is that the films are intended as vehicles for catharsis. There is inherent value in seeing a Jewish man fire machine gun rounds into Hitler’s face, or in seeing a freed Black man slaughter his former slaveowners. It’s a value I recognize: I do indeed take tremendous pleasure in the Bear Jew’s bashing of Nazi officers. But it strikes me that there is something cheap, and fleeting, about this justification. Fuck the Nazis is a satisfying thought, but rings hollow as soon as the end credits start to roll.

Django Unchained (2012)

Catharsis implies reciprocity: something unjust has already happened to me, and I take pleasure by responding in kind. The real value of Tarantino’s historical manipulations, I believe, stems from what we learn of our values when we imagine that unjust action never occurred in the first place. Django Unchained is not meaningful because we get to watch slaveowners die, but because we get to see Django reunited with the love of his life. Inglourious Basterds is not valuable because Hitler is killed, but because the Jewish soldiers triumph, and Shosanna (Mélanie Laurent) lives. It is difficult to see the value of things that never were, and Tarantino’s films are innovative because they make those alternate possibilities apparent. In this way, his movies are not ahistorical at all, but are in fact a corrective to the limited perspective with which we recall the seemingly immutable past. It is not so different, after all, from how war films are always about the lives that were saved. Whether based in reality, fiction, or something in between, we tell the stories we want to see.

This does not mean Tarantino’s mode of historical revision is without its pitfalls, however. Movies are so widely popular that they hold the potential to not only tell history, but create it. Might audiences someday believe that Charles Manson did not kill Sharon Tate, because that’s what happens in Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood? The answer is likely no, and the hope would be that general knowledge of historical truth will win out, especially given that the film binds the fates of real-life figures to fictional ones. But the possibility remains.

Moreover, the story must remain respectful to the real-life figures involved. Inglourious Basterds falters when Tarantino’s self-satisfaction in his moviemaking prowess overshadows the movie’s historical context, and Django Unchained is the weakest of the three because of the unease that comes with Tarantino’s flippant use of the n-word in the context of American slavery, and his baseless confidence that he should be the one to tell that story at all.

Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood (2019)

In this respect, Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood stands out as the strongest of Tarantino’s historical remakes (and his best film overall since 1997’s Jackie Brown). The ending of the film finds Charles Manson and his conspirators trespassing not on the property of Sharon Tate but of her neighbor, the fictional actor Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio). Rick’s stuntman Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) is there to greet them, high on acid, and he’s so loopy that we are sure his fate is sealed. But the scene ends with Rick and Cliff brutally slaughtering the Manson clan, saving themselves and Mrs. Tate in the process.

It’s a thrilling scene for many of the reasons Tarantino set pieces are often thrilling: the raucous music, the over-the-top violence, the humor, the unexpected little touches that make perfect sense in hindsight. But it’s also one of Tarantino’s most tender historical manipulations, because the film up to that point had given the audience a sense of Tate’s daily life. She goes shopping for a book for her husband; she gives a lift to a hitchhiking hippie; she’s overjoyed to see herself in a movie on the big screen. It’s one of Tarantino’s few historical corrections that is the removal of an action, rather than the creation of one. He is not going out of his way to kill Hitler, but rather to save the life of Sharon Tate. In doing so, it’s much more emotionally affective, and respectful of the life Tate lived. Tarantino has said he grounded her character in these actions to allow Tate not to be defined by her murder, and her sister has given Tarantino’s portrayal of Tate her blessing.

This representation of Tate also imbues the ending with a deep melancholy. After the Mansons have been offed, Rick stops by Tate’s home to fill in his neighbors on what happened. Tate laments how awful the ordeal must have been and the moment is crushing, because it still really did happen to her. In this sense, Hollywood goes well beyond the emotional depths of Basterds and Django: it not only offers an alternate vision, but mourns the loss that was.

It also helps that the Manson murders take up a very small proportion of the run time in Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood. The tragedy serves as an entry point for Tarantino to affectionately depict a bygone era, perhaps an era that never really existed except in nostalgic recreation. What stands out most about his vision of Hollywood in 1969 is not the fashion, or the cultural references, or any celebrity cameos. It is the leisurely pace at which life seems to move. The streets are quiet, and sparsely populated; the loudest noise we hear comes from the car radio. Rick struggles with his sense of self-worth in the movie industry, but for the most part, everyone seems content. The Manson murders represent the loss of this simpler time, and the prevention of those murders are a lamentation of how great it would be if we could only go back to that era. It’s a loving, wistful reflection on the past.

Cliff, the one ultimately responsible for preserving this past by stopping the Manson murders, is burdened by the ambiguities of fact typical of Tarantino characters. It is revealed midway through the film that he has supposedly gotten away with the murder of his wife. Tarantino gives us a glimpse of the scenario in flashback: Cliff’s wife tries to pick a fight with him as the two of them are on a boat in secluded waters; Cliff holds a harpoon in his hand. It is left purposely uncertain as to whether Cliff did, in fact, kill his wife, and other characters are left to quibble about whether the rumor is to be believed.

But to quote Landa from that opening scene in Inglourious Basterds, “However interesting as the thought may be, it makes not one bit of difference to how you feel.” The truth behind Cliff’s past, and the veracity of Tarantino’s entire depiction of Hollywood in 1969, is beside the point. The way the film made me feel is what matters, and it evokes a blend of nostalgia, joy, and melancholy. In that respect, Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood is a triumph.