‘Die Hard’ isn’t just a Christmas Movie. It’s the most Christmas Movie.

By Jake Skubish

It’s the holiday season, and you know what that means: stressing about gift-giving, never seeing your friends again till the spring because it’s too cold outside, and debating whether Die Hard is a Christmas movie.

Conan is right that this same argument keeps coming back up; it’s currently making its annual resurgence. But I don’t think it’s true that non-Die Hard fans don’t care. I’m usually met with sharp opposition when I declare Die Hard my favorite Christmas Movie. The rift over the 1988 Bruce Willis action classic has gone from quaint cinematic disagreement to bitter feud. On one side are the Christmas Movie Traditionalists, who argue that Die Hard is a heist movie released in July that just happens to take place on Christmas Eve. On the other side are the Believers, who argue that upon closer examination, Die Hard is really all about Christmas.

At least, that would be the ideal platform of the Believers. But the group is routinely much, much more annoying than this. In a 2013 article titled “Stop Saying "Die Hard" Is Your Favorite Christmas Movie,” BuzzFeed Reporter Katie Notopoulos argues that calling Die Hard a Christmas Movie is really just a pretense for being a pompous asshole. “There's a certain smugness of sneaking by on a technicality: well, technically the movie takes place on Christmas Eve, so it counts as a Christmas movie,” Notopoulos writes. Notopoulos would like Die Hard fanboys (and it is boys, mostly) to know that this take is “not only wrong,” but also “extremely commonly held.”

It would be disingenuous to pretend that this smugness is not a large motivation for Believers. It would also be dishonest if I didn’t admit that I have fun being coy about Die Hard as a Christmas Movie, too; Christmas Movie Traditionalists are just so indignant about it. But I am also a True Believer — I know that Die Hard is a Christmas Movie. I imagine this is what being a lifelong Warriors fan is like - your dedication is genuine, but you can’t avoid being associated with the recent, insincere bandwagon fans.

I also believe, however, that I am not alone in my convictions. There are many True Believers out there, but we have been drowned out by a dispute that is at best fractious and at worst outright hostile.

So let’s conduct an in-depth examination of Die Hard’s merits as a Christmas Movie. Although I believe in all of these arguments, I’m going to move from least compelling to most compelling argument for the sake of suspense, and also so by the end you hopefully agree that Die Hard is not just *a* Christmas Movie, but *the most* Christmas Movie.

One more side note: I’m setting aside the fact that Die Hard is already widely (though not universally) considered to be included in the canon of Christmas Movies. I actually think this is important — I think the very fact that people consider a film a Christmas Movie and make a habit of watching it every December is a meaningful indicator. But since this is the question we are trying to settle at all, I won’t include it. Although I guess I just kind of did.

Anyway. Let’s get started.

John McClane is a Christ-like figure

This category is by far the biggest stretch. I also think it’s a lot of fun, and maaaaaaybe has some merit.

Christmas is not just a celebration of American consumerism; it also happens to be a religious holiday about a man named Jesus Christ. Die Hard references things related to Mr. Christ a lot, and maybe suggests that John McClane (Bruce Willis) is Christ, or something like him. Let’s review:

The word “Jesus” is said eight times. This includes a shot at the end of Die Hard in which John emerges from the shadows to confront Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman), and upon seeing him John’s wife Holly (Bonnie Bedelia) gasps “Jesus,” as if she is referring to John himself.

Aside from the word Christmas, which I’ll get to later, the word “Christ” is said nine times. This includes a moment in which John discovers that Holly has changed her last name, information which makes him mutter “Christ,” which is also a last name. This is suspicious timing.

Holly says to John of her co-worker Ellis (Hart Bochner) at one point that “He thought he was God’s greatest gift.” She emphasizes the first “he,” implying that perhaps someone else she knows is, in fact, God’s greatest gift. John replies “I know the type,” implying that he can relate to Ellis’s sentiment.

McClane tells Sgt. Powell (Reginald VelJohnson) that his survival is “up to the man upstairs,” which is a great line because it’s obviously a reference to God but also Hans Gruber is literally upstairs in the building.

McClane kills 12 terrorists.

Die Hard features two pregnant women: Powell’s wife and Holly’s assistant Ginny (Dustyn Taylor). This seems abnormally high for an action movie.

McClane is running around in white garb and bare feet, which the movie makes a point of calling attention to.

I recognize this is flimsy evidence, and sounds like a crazy theory, and probably means nothing. But the idea that John makes Christ-like sacrifices is one that the film’s screenwriter has proposed himself. And who would know better than the guy that wrote the character?

Christmas music

Any great Christmas Movie will have Christmas music, and Die Hard is no exception. The film features four classic Christmas songs: “Winter Wonderland,” “Let It Snow,” “Christmas in Hollis” by Run-DMC, and “Jingle Bells” (although not officially played during the movie, Willis whistles “Jingle Bells” when he first walks into Nakatomi Plaza).

Mentions of Christmas/Christmas-related things

Any true Christmas Movie will obviously reference Christmas or Christmas-related things many times. Die Hard has this covered. A meticulous viewing of the film produces the following facts:

The word “Christmas” is said 18 times. I didn’t compare this to other Christmas movies, but that has to be more than a lot of them.

These are not just simple mentions of the holiday. They often come at critical points in Die Hard. There is Theo’s (Clarence Gilyard Jr.) riff on “‘Twas the night before Christmas” as the SWAT team closes in on the building. There is Gruber’s assurance that the plan will go well because “It’s Christmas...the time of miracles.” And when Theo finally opens the vault, he looks at the bearer bonds in awe as he says “Merry Christmas,” easily the greatest gift unwrapping sequence in Christmas Movie history.

Classic Christmas figures Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, Ebenezer Scrooge, Frosty the Snowman, and Santa Claus are each mentioned once.

John’s wife is named Holly, a clear reference to having a holly jolly Christmas.

John’s McClane’s limo driver is named Argyle, a clear reference to wearing argyle sweaters during the Christmas season.

And there is, of course, the classic “Now I have a machine gun, ho ho ho” shot.

Takes place during Christmas

If we count Christmas Eve as part of the Christmas holiday (which we should, both for the holiday’s religious origins and for the basic logical fact that it’s the rare night before a holiday that has a proper name), then 100% of Die Hard takes place during the Christmas holiday. This makes the film a virtual lock as the all-time leader in this category. Also, in a very scientific study I conducted by scrolling through movies streaming online, this puts Die Hard 60% above total runtime for It’s a Wonderful Life (53 minutes of Christmas time) and 80% above White Christmas (25 minutes of Christmas time).

Minutes that take place during Christmas Holiday

Christmas is integral to the story

Even if Christmas Movie Traditionalists concede that Die Hard takes place entirely on Christmas Eve, they will often contend that it doesn’t matter. Christmas is incidental to the plot, they say. Die Hard could take place on any other day of the year and it would be the exact same movie. Four responses to this:

The fact that it’s Christmas is essential to the plot. Hans Gruber’s plan to rob Nakatomi Plaza is dependent on it being Christmas Eve. Gruber planned on using the hostages as a negotiating tool with the FBI, and also planned on questioning Mr. Takagi for a passcode to the vault. So he needed a time that was after working hours and would have the employees of the 30th floor in the building (right when they arrive Theo locks the first 29 floors of the building, confirming they were targeting that floor specifically).

This leads to the Christmas Movie Traditionalists’ inevitable follow-up: yes, but it didn’t necessarily have to be a Christmas party. This is a bad argument for multiple reasons, which I’ll get to, but I’ll start with the fact that it is highly unlikely any other event, let alone any other holiday, would have kept these employees in the building after work. Any work-related event would likely happen during working hours, and any casual get-together would likely happen at a bar or restaurant or someone’s home, not in the lobby. It had to be a coordinated social function, which leads to holiday parties.

And honestly, are there any other holidays that people would stay at the office after work for? The Fourth of July and Memorial Day are strictly outdoor holidays, Thanksgiving is based on family dinners, and no other holiday is really celebrated enough to suffice an office gathering. New Years Eve is the only other possibility, and that’s a real stretch. An office Christmas party isn’t just a convenient event for Gruber to hold hostage; it’s also the only I can think of that would work and would occur regularly. There was literally a movie called Office Christmas Party a couple years ago, because the trope is that well recognized.

Also, one of the most well-known scenes in Die Hard involves John McClane taping two guns to his back and then laughing very mechanically so he can sneakily shoot Hans Gruber. The tape holding those guns to his back? Christmas wrapping tape.

The fact that it’s Christmas is essential for thematic purposes. I will get to this more in a bit, but let’s just say that Christmas Movie Traditionalists need to look past the basics of the plot. Die Hard is a movie about the true meaning of Christmas.

This is a dumb argument that doesn’t even apply to a lot of other Christmas Movies. The previous two responses would prove Christmas Movie Traditionalists wrong anyway, but we should take a deeper look at this argument, because when you do you see that it is a very dumb argument.

The plot doesn’t depend on the fact that it’s Christmas? What Christmas movie does? The only reason George Bailey tries to kill himself on Christmas Eve is because that’s when Uncle Billy happens to lose $8,000 that belongs to Bailey’s business. (Side note: $8,000 in 1946, the release year of It’s a Wonderful Life, would be worth $94,096.74 today. Uncle Billy messed up big time.) Bailey could have easily learned his life was worth living in April.

Home Alone could have easily been about Macaulay Culkin fending off intruders on any other day of the year. Those people could have fallen in love in Love Actually on another holiday (this is basically the movie Valentine’s Day). Even Buddy the Elf could have reconnected with his father during another time of the year! Christmas helps, but it’s not essential.

This is a dumb argument because of Halloween Movies. Halloween Movies provide a nice analogy for why this “Christmas needs to drive the plot” argument is silly. There are many movies widely accepted as Halloween Movies, like A Nightmare on Elm Street or The Shining, that have virtually nothing to do with Halloween. But they are accepted as Halloween Movies because they encapsulate the spirit of the holiday: fear. The same goes for Christmas Movies: Christmas should be a part of them, but they fundamentally need to be about the meaning of Christmas.

Intended to be a Christmas Movie

In law, there are different punishments for killing someone. If you did it by accident, you get a lesser charge. But if your intent can be proved, you get a harsher one. We can apply the same principle to Christmas Movies: if it can be shown that a movie was meant to be a Christmas Movie, then it is probably a Christmas movie.

This category is crucial to a movie being a Christmas Movie. With most Christmas Movies, we don’t even have to investigate this: if Santa is a character or the word “Christmas” is in the title, it’s fairly obvious that it was meant to be a Christmas Movie. This category is really only important for movies like Home Alone, or Love Actually, or Die Hard, which are ostensibly about Christmas but don’t come right out and say it.

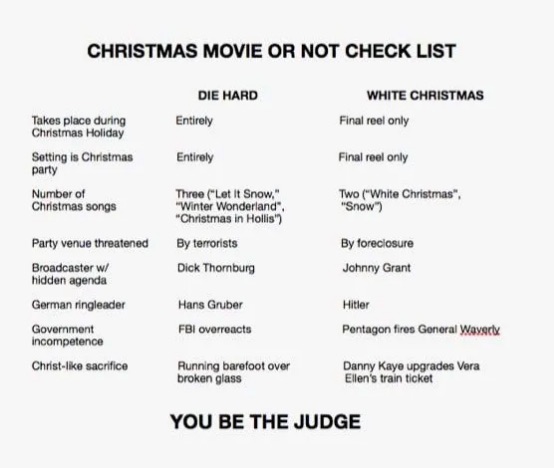

So it is a good thing that Die Hard clearly has intention on its side. Steven E. de Souza, the movie’s screenwriter, has been publicly adamant that Die Hard is a Christmas movie, and I can’t really think of any source more compelling than the guy who wrote the damn thing. To emphasize his point, de Souza created this compelling graphic:

There are two more key bits of information provided by de Souza. First, he recalls that the film’s producer, Joel Silver, declared that Die Hard would become a Christmas classic from the earliest moments of the film’s production. Second, de Souza also says that Nothing Lasts Forever, the book by Roderick Thorp on which Die Hard is based, is even more heavily about Christmas than his script (in the book, the climax takes place on Christmas morning). Honestly, if you take anything away from this article, it should be that Die Hard is somehow based on a book.

I have to acknowledge the glaring counterargument in this section: Bruce Willis himself said this July that Die Hard is not a Christmas movie. Who would know better than the man who played John McClane? Well, the man who wrote John McClane, for one. Also, Willis made this blasphemous claim during a celebrity roast, casting serious doubt on how serious he was when he said it.

The true meaning of Christmas

In the limousine ride from the airport to Nakatomi Plaza, Argyle pops a tape of “Christmas in Hollis” into the cassette player. John hears the rap song and asks Argyle, “Don’t you got any Christmas music?” Argyle responds, “This is Christmas music!”

The exchange is a suitable metaphor for how Die Hard functions as a Christmas Movie. More than anything, a true Christmas Movie must be about the meaning of Christmas. Halloween has scares and the Fourth of July has patriotism, but there is no holiday with which we imbue more meaning than Christmas. When Willis questions “Christmas in Hollis” as a Christmas song, he does so because it doesn’t sound like the classic old-timey jingle associated with Christmases past. That type of song, for John, was wrapped up in what it means to experience Christmas.

This, I think, is the main reason Christmas Movie Traditionalists exclude Die Hard from the Christmas movie conversation: it doesn’t adhere to traditional expectations of what Christmas looks like. Katie Notopoulos’s assertion that it is coy to suggest that Die Hard could be one’s favorite Christmas Movie implies a standard model of Christmas Movies to which Die Hard does not belong: musical numbers, a warm fire, a thick layer of snow. Traditional Christmas Movies have mistletoe. Die Hard has a machine gun.

But I think this is the very reason Die Hard is the most Christmas Movie of all: it has all of the emotional and thematic components of traditional Christmas movies, but transplants them into a thoroughly modern setting. Beyond its violent plot, Die Hard is a parable about one man’s devotion to his family, and the unconditional kindness of strangers. I don’t know that there’s even been a more compelling friendship on screen where the characters never actually meet (until the very end) than Powell and McClane. Both of these elements are on full display in the bathroom scene, one of the most emotional moments about family and friendship in any movie, let alone any Christmas movie.

And while other Christmas movies contain similar elements, they feel like relics of a distant American past. The Fourth of July might technically be the most American holiday, but Christmas is our most Americanized; all you need to do is look to the president’s griping about saying “Happy Holidays” to see how deeply Christmas has become a symbol of traditional American values.

Die Hard is representative of the American Christmas more than any other Christmas movie by a long shot. It’s a movie about a terrorist attack laced with latent xenophobia (the terrorists are an amalgam of ethnically ambiguous foreigners). It’s a movie that celebrates the recklessly overconfident, anti-authority lone cowboy archetype and makes two police officers its heroes. It’s a movie that glorifies violence, guns, greed, and money and portrays the media as inept and immoral. It’s a movie where the only food products consumed on screen are Twinkies, alcohol, a Crunch Bar, and Coca-Cola. There is literally a character named Special Agent Big Johnson.

It is this deeply American backdrop against with John must fight for his life and for his family. At the end of Die Hard, Gruber is hanging onto Holly for dear life, and John must unfasten her new Rolex watch in order to kill off Gruber. The film’s villain aptly meets his fate because our hero values family over consumerism.

Die Hard is a Christmas movie for the same reason “Christmas in Hollis” is a Christmas song: it captures the spirit of the season with a modern sensibility that feels more real than any hokey holiday tale. Die Hard is America’s Christmas Movie. We shouldn’t just be accepting it as part of the Christmas Movie collection; we should be anointing it as the best of them all.