Do the Oscars even matter? An investigation

By Jake Skubish

In 1989 Driving Miss Daisy won the Academy Award for Best Picture. The mushy historical drama about racial reconciliation via road trip is one of the most critically maligned Best Picture winners in history. This is a result of forces both intrinsic and external: revisionist critics have widely panned the film for its racial politics, but it has also taken a beating for what it beat out for its Best Picture win: the Spike Lee masterpiece Do the Right Thing.

“Beat out” is a loose term: Do the Right Thing wasn’t even nominated for the Academy’s top prize. Its omission is considered one of the most egregious in the 90-year history of the Oscars. And with obvious parallels to the potential of this year’s critically maligned mushy historical drama about racial reconciliation via road trip, Green Book, besting a diverse slate of movies that includes yet another Spike Lee film (BlackKklansman), critics are worried that the Academy will once again make the wrong choice.

Meanwhile, the Do the Right Thing fanbase seems much more up in arms about Spike’s loss than the pioneering director himself. “When Driving Miss Mother-fucking Daisy won Best Picture, that hurt,” Spike told New York Magazine in 2008. “No one’s talking about Driving Miss Daisy now.” It’s a refrain he’s repeated since: he’d like to have an Oscar, but he knows Do the Right Thing is being taught in schools across the country. It has been canonized.

Isn’t that supposed to be the whole point of the Oscars? To anoint a cinematic hierarchy, and to honor and immortalize the great films? The tone among Oscars prognosticators is consistent these days: the Oscars are silly and self-congratulatory, but we still talk about them because they matter, and they matter because the bequeathment of an Academy Award renders a movie worthy for future generations to seek out. The Academy, the reasoning goes, is a tastemaker.

Which got me thinking: is that true at all? Why do we assume this stuff matters? So I set out to look at some data and try to determine if the Oscars are really worth all the fuss.

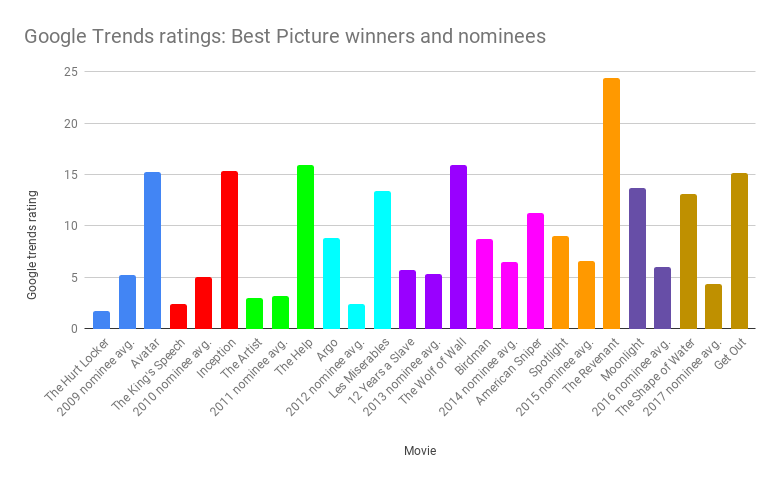

First up: Google. If the Oscars are a tastemaker then they should affect which movies people seek out the most, and no better place is an aggregator of such information than Google Trends. By comparing the nominees of each year on Google Trends you can get a metric measuring how much each of those films was searched on Google compared to one another on a convenient 100-point scale.

I did this for the past 25 years of nominees. Google Trends data only goes back to January 1, 2004, so for pre-2003 films I searched for this entire time-span, and for post-2003 films I searched for results starting on the day of that year’s Oscars ceremony. The results are below in two charts: one from 1993 - 2008 and one from 2009 - 2017. (2009 was the year the Oscars expanded the Best Picture field from five to between five and 10.) If a nominee was searched for more than a winner in a given year, I included it in the chart.

1993 - 2008

The takeaway:

The Best Picture winner has only been the most searched for film of its year 11 of the past 25 years.

There is a historical self-correction of sorts going on among the most infamous Oscar upsets: Brokeback Mountain is searched for more than Crash, and Saving Private Ryan is searched for more than Shakespeare in Love.

There is a crucial split from 2008 to 2009. In 2009, the Academy expanded the field of nominees from five to anywhere from five to ten. This decision came in large part as a response to the Oscars’ exclusion of The Dark Knight in 2008, a film beloved by audiences and critics alike. Following that debacle the Academy made a concerted effort to include the type of popular movies people loved and critics respected. The result? Since 2009, only one Best Picture winner was the most searched for movie of its year: the universally beloved Moonlight. This split suggests that any ability the Academy had before the expansion to honor the most searched for movie was less a sign of taste-making than elitism: if they had previously included more of the types of films people love, the chart would look a lot different. (This point is reinforced by the fact that the first two Lord of the Rings films outperformed the winners of their respective years before The Return of the King won Best Picture.)

But what happens if we turn to a more cinema-focused database than Google? Below are the three most popular movies per year of the past 25 years among IMDb users:

| Year | Most popular that year | Best Picture winner | Best Picture winner popularity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | Jurassic Park, Schindler's List, Tombstone | Schindler's List | 2 |

| 1994 | Pulp Fiction, The Shawshank Redemption, Forrest Gump | Forrest Gump | 3 |

| 1995 | Se7en, Heat, The Usual Suspects | Braveheart | 4 |

| 1996 | The Birdcage, Romeo + Juliet, Mars Attacks! | The English Patient | 16 |

| 1997 | Titanic, My Best Friend's Wedding, Good Will Hunting | Titanic | 1 |

| 1998 | The Big Lebowski, The Wedding Singer, Saving Private Ryan | Shakespeare in Love | 18 |

| 1999 | American Pie, The Matrix, Eyes Wide Shut | American Beauty | 7 |

| 2000 | Unbreakable, Requiem for a Dream, Gladiator | Gladiator | 3 |

| 2001 | Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, American Pie 2 | A Beautiful Mind | 11 |

| 2002 | Scooby-Doo, Spider-Man, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets | Chicago | 14 |

| 2003 | Love Actually, The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King, Big Fish | The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King | 2 |

| 2004 | The Incredibles, The Notebook, Troy | Million Dollar Baby | 24 |

| 2005 | Pride & Prejudice, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, The 40 Year Old Virgin | Crash | N/A (16) |

| 2006 | Casino Royale, The Departed, The Prestige | The Departed | 2 |

| 2007 | Hairspray, No Country for Old Men, Zodiac | No Country for Old Men | 2 |

| 2008 | The Dark Knight, Twilight, Taken | Slumdog Millionaire | 10 |

| 2009 | Avatar, Inglourious Basterds, Watchmen | The Hurt Locker | N/A (21) |

| 2010 | Valentine's Day, Inception, How to Train Your Dragon | The King's Speech | 28 |

| 2011 | Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Captain America: The First Avenger | The Artist | 74 |

| 2012 | Django Unchained, The Hunger Games, The Dark Knight Rises | Argo | 31 |

| 2013 | Frozen, The Wolf of Wall Street, Prisoners | 12 Years a Slave | 5 |

| 2014 | The Lego Movie, Interstellar, Guardians of the Galaxy | Birdman | 14 |

| 2015 | The Lobster, Sicario, Fifty Shades of Grey | Spotlight | 17 |

| 2016 | Split, Suicide Squad, Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them | Moonlight | 8 |

| 2017 | Happy Death Day, The Greatest Showman, Get Out | The Shape of Water | 7 |

The takeaway:

Titanic is the only Best Picture winner of the past 25 years to be the most popular of its year on IMDb.

According to IMDb Crash was released in 2004 and The Hurt Locker was released in 2008, but they won Best Picture in 2005 and 2009, respectively. The numbers listed are their rankings for 2004 and 2008, respectively, not the years for which they won Best Picture.

In nine instances, the Best Picture winner didn’t crack the top ten.

The most popular films consist of the types of films popular among critics and audiences, like The Dark Knight, that the Academy tends not to award. Jurassic Park, The Big Lebowski, Se7en, The Incredibles, Casino Royale, The Dark Knight, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2, Frozen, and The Lego Movie are all modern classic that didn’t even earn a Best Picture nomination, but are the most popular of their year on IMDb.

The caveat here is two-fold: there is pretty apparent recency bias (Valentine’s Day, for example, will not this far up if I check back in July), and popularity represents some combination of recency and total pageviews; it is not organized by highest user rating.

Luckily, IMDb allows us to look at that data. The site’s exalted top 250 list gets all the attention, but you can actually look as deep as the top 1000 rated movies on IMDb. So, we can take a look at how many of the Best Picture winners make that list, an indication of their staying power among audiences.

The takeaway:

In one sense, this is a good look for the Oscars. 59 of the 91 Best Picture winners are represented on this list, and the highest share of those films is in the top 200. The Oscars are especially well represented at the very top: four of the top ten are Best Picture winners.

On the other hand, all of those four (The Godfather, The Godfather Part II, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, and Schindler’s List) were already massive box office hits among audiences before the Oscars ceremony. Audiences only consider 40 Best Picture winners to be among the 400 greatest movies ever made, and most damning, 32 of the Best Picture winners aren’t even among audiences’ 1000 highest rated movies. Not a signal that the Academy is a strong tastemaker.

But forget about audiences. What about critics? Surely if the Academy influences what we consider to be the great movies, then a respectable critical retrospection on the great movies will feature a large share of Best Picture winners.

The most respected critical survey is the Sight & Sound poll, of which Roger Ebert once said “Because it is world-wide and reaches out to voters who are presumably experts, it is by far the most respected of the countless polls of great movies--the only one most serious movie people take seriously.” The most recent iteration, in 2012, was comprehensive, with nearly 850 experts in the film industry surveyed. The Sight & Sound critic’s survey features just five Best Picture winners: Sunrise, The Godfather, The Godfather Part II, Lawrence of Arabia, and Casablanca.

But what if we set aside audiences and critics for a moment? What if we turn to an institution that doesn’t honor the movies it liked the most, but the movies it deemed the most important? I’m talking, of course, about the Library of Congress National Film Registry.

Per the National Film Registry’s own description, the collection of films is “a list of films deemed "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant" that are recommended for preservation by those holding the best elements for that film, be it motion picture studios, the Library of Congress and other archives, or filmmakers. These films are not selected as the 'best' American films of all time, but rather as works of enduring importance to American culture. They reflect who we are as a people and as a nation.”

This might be the best measure yet of the Academy’s influence: the National Film Registry literally immortalizes the movies determined to be the most influential. If Best Picture winners are influential, they should appear on this list. But of the more than 600 titles in the Registry, only 46 of the eligible 81 Best Picture winners (films are not eligible for the National Film Registry until 10 years after their release) make the list. By raw number that might seem large, but think about what that means: The Library of Congress doesn’t even think nearly half of the Best Picture winners are culturally significant enough to be preserved.

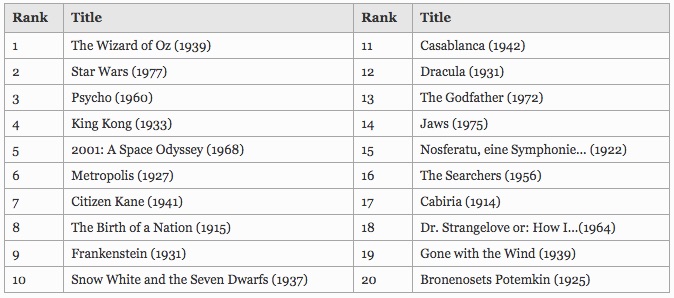

An interesting note on the National Film Registry: a few years ago, a group of researchers conducted a study to determine what factors earned a film a spot on the Registry at all. Their conclusion? The biggest predictor of placement in the Registry wasn’t box office success, critical reception, or audience approval. It was the frequency with which other films and filmmakers borrowed from or referenced a movie in some way. In other words, influence was evident in how much a film impacted future films. Per the researchers’ methodology, these are the 20 most influential movies of all time:

And it’s a list that makes a lot of sense, right? It would be hard to argue with that top five being the five films that will still be remembered a century from now. Of that top 20 list, three are Best Picture winners: Casablanca, The Godfather, and Gone with the Wind.

I think what we can take away from all of this is that the Oscars have some influence/predictive power about the movies that will be remembered, but are not at all the tastemaker they imagine themselves to be, or that we make them out to be with the disproportionate amount of attention we give their decisions. Looking at all of these lists, it is clear that the process of cinematic immortalization is amorphous, and imprecise, and something mostly up to the masses to determine. We make our own classics.

Which is why it’s interesting now to note one contrast in particular on the National Film Registry: Do the Right Thing is in the Registry, and Driving Miss Daisy is not. Spike’s intuition was right: Driving Miss Daisy may have been awarded in 1990 and his film may not have even been nominated, but only his is still relevant in the culture. So while it’ll be fun to participate in the outrage on Twitter if the Academy gives Green Book a Best Picture win, fear not. Fight for and promote the movies you love the most, because the Academy doesn’t decide what goes down in history anyway.