The exploitative fiction of ‘Blonde’ and the legacy of Marilyn Monroe

By Jake Skubish

Ella Fitzgerald once said of her friend Marilyn Monroe, “She was an unusual woman — a little ahead of her times. And she didn’t know it.” If Monroe’s remarkable accomplishments as a boundary-pushing, culture-defining public figure couldn’t quite be made sense of in the 1950s, then perhaps her time is 2022, where her image is having something of a renaissance (if the image of Marilyn Monroe could ever really wane).

At the Met Gala in May, Kim Kardashian revived Monroe’s iconic crystal-studded dress, worn during her 1962 “Happy Birthday” serenade to President John F. Kennedy at Madison Square Garden. A week after Kardashian’s stunt, Andy Warhol’s famed 1964 portrait of Monroe sold for $195 million at Christie’s auction house, shattering the record for American artwork sold at auction. Both instances — in which Monroe’s body and image are stripped of context and packaged for mass consumption — are typical of the pattern in which her likeness is continually resold.

Then there are the representations on film. Monroe was the subject of two major documentaries this year, both perhaps trying to ride the coattails of the attention now being generated by Netflix’s glitzy adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ Marilyn Monroe novel, “Blonde.” The Blonde film has been in the works for more than a decade, but it feels fitting that it is arriving now, a tidal wave within the ocean of content trying to claim authority on the meaning of Monroe’s life 60 years after her tragic death.

Any attempt to try and replicate the singular aura of Monroe, perhaps the most captivating screen presence in the history of Hollywood, is an endeavor doomed to fail. With Blonde, however, director Andrew Dominik and star Ana de Armas have an out: They are not attempting to portray the real Monroe, but rather the fictionalized inner life of Monroe as conjured by Oates’ novel. In this sense their job is easier, if more dubious: using the life of an American legend as the basis to tell a moral tale about Hollywood’s failures in a larger sense. They are less striving to tell the truth about Monroe than the (eye roll) truth about society.

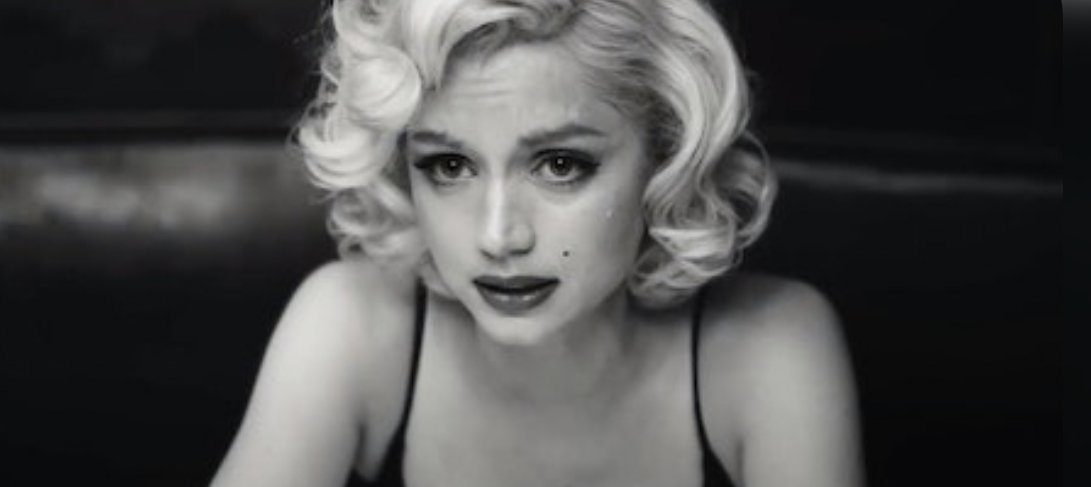

de Armas in Blonde

I’ll cut right to the chase: “Blonde” the novel is a demeaning, condescending, and ethically vacant work of exploitative bullshit, and Blonde the film is even worse. Oates’ book clears the bare minimum moral bar by announcing on the cover that it is a novel; however reductive her narrative is, Oates is at least acknowledging that it is baloney. But Dominick's film from the beginning makes no such acknowledgement, and neither the film’s much-watched trailers nor any part of the feature film itself acknowledge that the story being shown on screen, while drawing from real-life figures and events, is largely an invented work of fiction. There are too many inaccuracies in the depiction of Monroe’s life in Blonde to list, but suffice it to say that if you are looking for what really happened during Monroe’s illustrative life and career, Blonde is not the movie for you.

As Netflix beams this film into the homes of its more than 220 million subscribers, many are going to take as truth the falsehoods presented in Blonde. Oates has proclaimed her wretched novel is a restitution of Monroe’s image, but with the invasion of Blonde onto Netflix, the iconic actor’s story needs a correction more urgently than ever.

I’m not so naive as to think that everything in a film needs to be true. In fact, the whole enterprise is founded on stories that are fundamentally make-believe. But Blonde is a different sort of beast — a tangled mess of reality and fiction in which real people appear, some events are entirely made up, and other events are left out to satisfy Oates’ narrative interests.

That broader narrative is the heart of the problem with Blonde. It can be rational, and even admirable, to toy with the details in order to serve a greater truth in the process. But when the facts are dismissed in pursuit of a narrative that is reductive and degrading, what’s the point?

Oates’ goal with Blonde is to use Monroe’s life and career as a vessel for a story about the abuses and violence perpetrated by powerful men, and in some ways she succeeds. Monroe certainly entered into a misogynistic Hollywood system and had to endure very real abuses and indignities on her path to stardom. Broadly speaking, this is a story that deserves to be told. But in centering the power of men who want to hurt Monroe, Blonde denies the agency of the woman whose legacy it claims to be rectifying. A nonstop parade of men infantilizing Monroe becomes itself infantilizing, refusing any perspective that might show Monroe making her own choices or having her own thoughts. It’s telling that the introduction of Oates’ novel notes the author was inspired to write it not by learning anything about Monroe’s life but by seeing a childhood photo of Monroe and wondering how she became a national icon. “Blonde” is an unabashed act of projection with little consideration for the authentic life of its subject.

The film is two and a half hours of unyielding suffering for Monroe, and Dominik’s camera takes great pleasure in watching her squirm. What was supposedly meant to be a correction instead tells the same old tale about Monroe, making her entire life out to be pain and tragedy. Blonde embarrassingly creates a story in which everything happens to Monroe, grafting a story of inescapable abuses onto the life of a woman who broke barriers and wielded her own power and intellect to firmly take hold of the choices in her career.

Dominik, who has been attached to the film adaptation since its inception, is in alignment with Oates’ deficit framework. In the early stages of the project’s development, Dominik said he saw Monroe as “an orphan child lost in the woods of Hollywood, being consumed by that great icon of the twentieth century.” This structure defines the film and de Armas’ performance, in which Monroe is seen as a cowering child. This version of Monroe is insultingly simple-minded; she is often shown to be confused and unable to process what is going on around her. (A representative line from the novel, as Monroe’s fame skyrockets: “Oh! — is this happening to me? What is this that is happening to me?”)

Perhaps this depiction would have been easier to stomach if the movie itself were an entertaining affair, but Dominik’s Blonde is flat, a two-and-a-half hour slog. It plays like a horror film without any suspense, a catalog of made-up events with no energy. If nothing else (and it is nothing else), Blonde is somewhat impressive as an act of visual mimicry in the scenes where de Armas is placed into classic Monroe scenes. But this pastiche is ultimately pointless; why not watch these wonderful films themselves?

In Blonde the invention of “Marilyn Monroe” is a burden thrust upon Norma Jeane, rather than an image she actively shaped to advance her career. Her path is determined by a traumatic childhood, which Dominik captures early in scenes so overwrought and filled with groan-worthy foreshadowing they recall the “Wrong kid died!” energy of Walk Hard.

In reality, Monroe was determined to become a successful actress from the earliest stages of her career and took acting classes since the late 1940s, little of which is visible in Blonde. She is instead presented as someone who is conjuring magic on camera either by total accident or as a response to past traumas, rather than as a craft she continually worked on. The film is entirely dismissive of her considerable acting talents.

Monroe in New York after announcing Marilyn Monroe Productions, 1955

Even more egregious is the omission of Marilyn Monroe Productions, a production company Monroe started in 1955 at the age of 29, nearly unheard of for a woman in that era of Hollywood. Monroe started the production company in the aftermath of the success of The Seven Year Itch, which earned 20th Century Fox an enormous box office return even as Monroe was locked into a low-salary contract. After Itch the studio set her up for a comedy she thought had a weak script, and when she found out how much less she was getting paid than costar Frank Sinatra, she walked off the set, moved to New York, and announced her own production company.

The studio sued Monroe but she continued her holdout while training at the Actors Studio. By the end of the year, after unsuccessfully trying to replace Monroe, Fox gave her a new $100,000 per movie contract, gave her director approval over any movie she signed onto, and let her make movies through her own production company. Monroe went on to make more movies for the studio and made The Prince and the Showgirl, a terrific comedy featuring what might be her best performance, through her own production company. The creation of Marilyn Monroe Productions was a powerful move by Monroe and a watershed moment for pay equity. Neither Marilyn Monroe Productions nor The Prince and the Showgirl get a single mention in Blonde.

Instead of focusing on these career accomplishments, Oates’ novel portrays Monroe as a perpetually worn-down victim of sexual exploitation — ignoring the ways in which Monroe proactively fought against Hollywood misogyny. In 1953 Monroe co-authored an article titled “Wolves I Have Known,” in which she called out the abusive behavior of Hollywood executives. This was a bold and transformative moment in 1950s Hollywood, yet in Blonde no such defiance is displayed by Monroe, only suffering at the hands of all-powerful men.

This sexual exploitation extends into the scenarios Oates entirely makes up. In Blonde, Monroe is raped by 20th Century Fox executive Darryl Zanuck. This is a fiction invented by Oates in her novel; there is no evidence this happened. This incident, however, is a critical moment for Monroe’s career in Blonde. When Joe DiMaggio (Bobby Cannavale) asks Monroe how she got her start, she flashes back to this assault.

It is true that there were times Monroe slept with producers early in her career — she says as much in her autobiography, “My Story.” Yet Blonde, in attempting to draw attention to abusive Hollywood executives, allows Monroe to be entirely defined by trauma rather than being someone who got her start in the industry because of her acting talent, and imposes on her a violent episode that never occurred.

(There is clear historical record, meanwhile, of Monroe losing out on a contract renewal at Columbia Pictures because she refused to sleep with studio head Harry Cohn. Invited by Cohn to join him on his yacht, Monroe asked if his wife would be there.)

The shame of Monroe’s sexualization is another prominent theme of Blonde, and Oates’ perspective is remarkably conservative and moralizing. In 1949 Monroe posed nude for a calendar, images which later became a scandal after she became a movie star. The Monroe in Blonde feels deeply ashamed of these photos. Yet in real life, Monroe said in an interview after the scandal broke, “I’m not ashamed of it. I’ve done nothing wrong.” Her ownership of this scandal allowed for it to be a moment of empowerment rather than embarrassment.

One of Monroe’s self-leaked images from the set of Something’s Got to Give

Monroe, in fact, knew how powerful a commodity her image could be and often deliberately used it to further her career. A decade after the calendar scandal, she was at risk of being dropped from the film Something’s Got to Give, which she was in the middle of filming when she died. So she orchestrated the distribution of semi-nude photos from the film (which she arranged to have taken on set), and the photos generated such interest in the film that she was reinstated at a new million-dollar contract. Blonde makes Monroe out to be a perpetual victim, someone who is ashamed of, or confused by, sexual autonomy. In the film she is “taught” about the potency of her sexuality by Charlie Chaplin Jr. and Edward Robinson Jr., with whom she is in a polyamorous relationship (again, untrue in real life). Blonde entertains no possibility that Monroe could have had any sort of sexual awakening on her own.

Perhaps the lowest moment in Blonde comes in the depiction of Monroe getting an abortion. There is not clear-cut evidence that Monroe had an abortion, but even more unethical than placing this event into Monroe’s life is how Blonde makes Monroe deeply regretful and ashamed after the abortion. At one point in the film Monroe’s CGI fetus asks her via voiceover why it was aborted, a moment so cringy and embarrassingly made it might be possible for one to miss its cruelty. It’s a condescending and revolting moment, and reveals how little respect Oates and Dominik have for Monroe. Oates’ stated crusade to save Monroe’s image might be taken more seriously if Blonde did not degrade its subject.

Blonde’s condescension extends into Monroe’s performances, the characterization of which make one wonder if Oates or Dominik ever actually watched her films. Monroe is often mistaken as having propped up the Dumb Blonde stereotype, a dismissive notion which ignores how wickedly smart and sex positive her characters were. More often than not she is making fun of the male gaze, and men are often the butt of the joke. Her characters could never really be perceived as dumb, because they were always charmingly one step ahead of the men around her.

Monroe in Some Like It Hot

Blonde portrays Monroe as having hated her role as Sugar Kane in Some Like It Hot and pulls a few lines out of context to make the role seem diminishing, even though she thought the part was terrific in real life and infused it with substance and depth. She was often a collaborator in making her characters more dynamic, none of which is seen in Blonde.

“I can be smart when it’s important,” Monroe says in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes as one of her most iconic characters, Lorelei Lee. “But most men don’t like it.” This line was added to the film after being suggested by Monroe herself, a signal that she was acutely aware of the intellectual high ground her characters stood upon.

The exceedingly negative outlook on every aspect of Monroe’s life in Blonde, from her career to her characters to her sexuality, adds up to a one-dimensional portrayal that exploits Monroe by ignoring any positives she had in her life. The film shamefully ignores, for example, the fact that Monroe had friends, instead framing her as entirely alone in the world. Her friendships with her producing partner Milton Greene or her acting coach Natasha Lytess? With jazz luminary Ella Fitzgerald or poet Carl Sandburg? Nonexistent in Blonde, because having positive relationships would not support the story Oates and Dominik want to tell.

Blonde is instead defined by a bogus feeling of tragic inevitability. Oates and Dominik strain to have Monroe’s end define everything that came before it. Early in Oates’ novel a character says of Norma Jeane, before she became Marilyn Monroe, that “already you could see the doom in her.” The book is full of foreboding language like this, as if Monroe’s premature death was evidence that she was always destined to be cursed. Yet her death should not define her — nor was it at all inevitable. Monroe spent weeks in 1962 at a drug withdrawal clinic, trying to get help, an event which is obviously not shown in Blonde. She was a remarkable woman who lived a remarkable life, and she died too soon, and that is deeply sad. But it should not color everything else that she accomplished during her impressive career.

Even uglier than the misguided motivations of Blonde is the outright conspiracy theory fodder of The Mystery of Marilyn Monroe: The Unheard Tapes, a documentary released by Netflix in April. The film is based not on any concealed evidence, as its title suggests, but on the interviews recorded by journalist Anthony Summers for his 1985 Monroe biography, “Goddess.”

To put it frankly: Do not watch this film if you have any respect for yourself or the truth. It is an embarrassing film for Netflix to have put its name on, and another vacuous product in the long tradition of seeing Monroe more as an object to be mined for content than as an intelligent, talented human being to be celebrated and studied. Consider a quote from Monroe that appears throughout the film: “True things rarely get into circulation.” This line is made to be an ominous refrain, flimsily propping up the film’s suggestions that what really happened to Monroe was sinister, or covered up. In reality, this quote comes from Monroe discussing how she landed on her iconic stage name. “I wanted my mother’s maiden name because I felt that rightfully it was my name, and true things rarely get into circulation,” Monroe says in the full quote. Her name was an act of agency and ownership over her legacy, which The Unheard Tapes willfully strips of context and which Blonde frames as a name forced upon her. Both Netflix films deny Monroe the agency of the choices she made throughout her life and career.

Anthony Summers, author of Monroe biography “Goddess,” in The Unheard Tapes

The Unheard Tapes stitches together conjecture, incomplete facts, and schlocky reenactments to make a grotesque spectacle of Monroe’s death. It cultivates a “mystery” out of thin air and then washing its hands of the whole endeavor by saying “But honestly, none of that probably happened” while still leaving in place a winking suggestion that maybe it did? It’s the filmic equivalent of a politician telling an audience during a debate, “Now, I’m not saying my opponent is a murderer,” when the very utterance of the suggestion makes the idea a possibility.

The Unheard Tapes makes the same lurid choice as Blonde, that of having Monroe’s death define everything in her life that came before it. But the documentary goes one step further than Blonde, indulging in long-disproved falsehoods and conspiracy theories to explain her death. Marilyn Monroe died of a barbiturate overdose, the consequence of an entirely common addiction at the time, particularly among celebrities who were liberally plied with the drugs. To suggest anything more nefarious is to make a mockery and a spectacle of a talented woman, and Netflix does not hesitate to indulge in this mockery.

As Monroe was well aware of with her own life, people are quick to mistake your on-screen persona as your true identity, a trap that Oates and Dominik repeatedly fall into with the version of Monroe presented in Blonde. By releasing these two pieces of fiction in tandem and not making it clear that neither is true, Netflix is actively encouraging its viewers to take away the idea that what they are seeing on screen is what really happened 60 years ago, all in service of absorbing our time and attention.

For a more accurate, complete, and human portrait of Monroe’s life, I recommend Reframed: Marilyn Monroe, a documentary series released by CNN in January, which provides a terrific overview of Monroe’s career accomplishments and a vital correction to the typical tragic, doomed narrative in which she is placed. Director Karen McGann positions the series from the very beginning in almost direct conversation with the nonsense of Blonde: “When we talk about Marilyn Monroe it’s always about poor Marilyn, poor Marilyn. This vulnerable, passive woman who is being destroyed by Hollywood,” a commentator remarks. “That’s the way the story frames her ... it’s time to reframe her story.”

And so Reframed does, quite successfully over the course of four episodes, as a series of Monroe biographers, experts, and friends (along with some elegant narration by Jessica Chastain) position Monroe as someone who was “an architect of her own fame.” The series presents a convincing account of how Monroe developed her own image, crafted layered and human performances, pushed the boundaries of sexual expression, and forced the studio system to bend to her demands. The film does not paper over the ways in which Hollywood routinely exploits women; it both recognizes this abuse and establishes how much of a force Monroe was in combating this culture.

Monroe, 1955

Reframed frequently turns to Marilyn Monroe in her own words, allowing her to speak on behalf of her own narrative in a way Blonde and The Unheard Tapes enthusiastically deny. “Because of the way Marilyn died we tend to look at her entire life as a tragedy,” a commentator says in the final episode of the series. “That simply wasn’t true.”

Reframed is a thoughtful, comprehensive, and necessary counter to the standard Monroe story. Yet even this outstanding series, which sticks to the facts and captures Monroe with reverence and grace, molds her life in the shape of the narrative it wants to tell, which becomes a bit sycophantic as it progresses. If Blonde condemns the apparatus of male violence at the expense of creating a fully realized female character, then Reframed is perhaps too bound by a modern narrative about trailblazing women kicking ass and taking names on an undeterred, ascendant path toward power and greatness.

That’s not to say that the film’s perspective on Monroe’s accomplishments is off-base — it’s not. It’s just to say that framing anyone in such an exalted light is a burden to carry. Positioning Monroe’s life as a tragedy is false and pernicious, but positioning her as unrelentingly ascendant is a more modest falsehood. Reframed largely glosses over Monroe’s widely known insecurities about her acting abilities; she was gifted and always striving to improve, but that doesn’t mean that she wasn’t unsure of herself. Most of the series’ attempts to reframe Monroe in a more active, positive light are factual and noble. But Reframed ignores some of the difficult realities of her life. To make her less complicated in this way is to make her a little less human.

Of course, any analysis of a historical figure like Monroe can only ever hope to capture an approximation of her life. But looking into Monroe’s personal writings offers a more honest insight beyond the public eye, and underscores the complexity, and often the mundanity, of her experience. “Fragments,” a published collection of Monroe’s notes, poems, and other first-hand documents given posthumously to Monroe’s acting mentor Lee Strasberg, offers the chance to glean these more candid observations.

Monroe, 1955

In some notes she laments the inability to truly connect with others: “Only parts of us will ever touch parts of others — one’s own truth is just that really — one’s own truth.” Other times she writes about how she is falling in love (“I think to love bravely is the best and accept — as much as one can bear”), or about her work (“Never miss my Actors Studio sessions”). The “Fragments” collection also includes the everyday notes one accumulates over a lifetime, recipes and shopping lists and plans with friends.

What stands out most in “Fragments” is Monroe’s struggle to make sense of the world around her. In a 1955 journal entry, she wrote: “The more I think of it, the more I realize there are no answers. Life is to be lived ... the only thing I know for sure, it isn’t easy.”

It’s these sorts of intimate details that offer a glimpse into the reality of Monroe’s life: an extraordinary life, yes, but also aimless in that way that any of our lives are. I think Monroe’s unending curiosity is why she resonates so much with me; even as she became one of the most significant Americans of the 20th century, she was always searching for meaning beyond the larger cultural forces that supposedly defined her.

Was her life about the rise of Hollywood, or the abuses endured by powerful women, or the dawn of the age of celebrity? Yes, and no. Her life can be about those things as long as we make it about those things, and I’m sure we will continue to do so. But in the end her life was filled with joy and sorrow like anyone else’s.

I think this is a useful thought exercise, to think about the meaning of my own life in a similar way, separated from the conditions that appear to provide its shape. Is my life about climate change, or consumer-capitalist culture, or living on the internet? Maybe, if anyone in the future cares to assign my life meaning. But none of these frameworks make sense as definitions for my own experience, because my life is only about how I live it each day. The magic of Monroe as a screen presence was that she made that daily experience feel meaningful, like every moment you spent with her mattered, even while winking at the viewer that yeah, none of this will last.

It is folly to have any one person bear the weight of all the social forces around them, whether positioning them as an exploited victim or a pioneer of social progress. As Monroe succinctly put it, life isn’t easy. But whatever meaning people continue to find in her story, it is a blessing to have her craft preserved on screen, to have into eternity her commanding aura that brought so much joy to so many. Her life and any of ours are up for debate, but what is certain is that to watch her films makes ours that much more of a gift.